William Wiman Part II

- By Gretchen Frick Small

- •

- 26 Jun, 2020

- •

In a previous blog (May 6, 2020), I mentioned William Dwight Wiman’s time in Europe, in 1886. During this trip, William spent time learning from Sir Francis Bolton. Bolton entered the Army at the age of 26, retiring in 1881 with the rank of Colonel. His service was notable as the inventor of the system of telegraphic and visual signaling. For these services and other inventions, the Queen conferred upon him the honor of knighthood. Following his retirement, he served as London water examiner under the Board of Trade, until his death in 1887.

During his time as water examiner, Bolton invented what was called the prismatic fountain. His invention became very popular as an attraction at exhibitions in England. He could manipulate the electric signals on a water fountain to create colored light shows in the mid-1880s.

Near the end of Sir Francis Bolton’s life is when William Wiman developed a friendship with Bolton and learned about his invention. As I mentioned previously, William Wiman returned to the United States and installed an electric fountain on Staten Island, but I had no proof of this.

Near the end of Sir Francis Bolton’s life is when William Wiman developed a friendship with Bolton and learned about his invention. As I mentioned previously, William Wiman returned to the United States and installed an electric fountain on Staten Island, but I had no proof of this.

Recently I came across a reference that states that Erastus Wiman (William’s father) was inspired by the success of Bolton’s fountain at the London Health Exposition in the 1884. Luther Stieringer wrote in “A Brief History of Luminous Fountain Development,” (c1900) that “Erastus Wiman arranged with Sir Francis Bolton to design an electric fountain for the St. George’s Amusement Company, of Staten Island, NY. The fountain so erected was installed and publicly operated in 1885, and it bears the distinction of having been the first luminous fountain seen in the United States”.

This statement makes me rethink the timeline of when and why William Wiman traveled to Europe and met Sir Francis Bolton. Just goes to show you that your research is never complete. What you have read in the past and always assumed was correct, can be changed with just one more source. That is until you come across something that contradicts what you have read.

So previously, I stated that William Wiman traveled to Europe in 1886 and met and learned from inventors including Sir Thomas Bolton. Now I am thinking that Erastus Wiman purchased a fountain for Staten Island. The invention intrigued his son William who then traveled to England to learn more.

Stieringer continues with a description of the Staten Island fountain, “The original design of this fountain showed a square masonry basin holding water to a depth of 4 ft. In this basin there were arranged 16 light shafts, while in the chamber beneath the color screens and other necessary apparatus were installed”. He also states that “Mr. Wiman became quite interested in fountain work and bought a patent from Sir Francis Bolton of a floating fountain capable of being sent to different harbors, or to river towns, there to be displayed as an attraction. However, no fountain embodying the ideas of the patent has ever been built”.

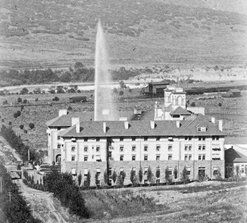

According to Stieringer, the Staten Island fountain did not operate that long, but was sold to Mr. Yerkes in 1886 to be erected in Chicago’s Lincoln Park.

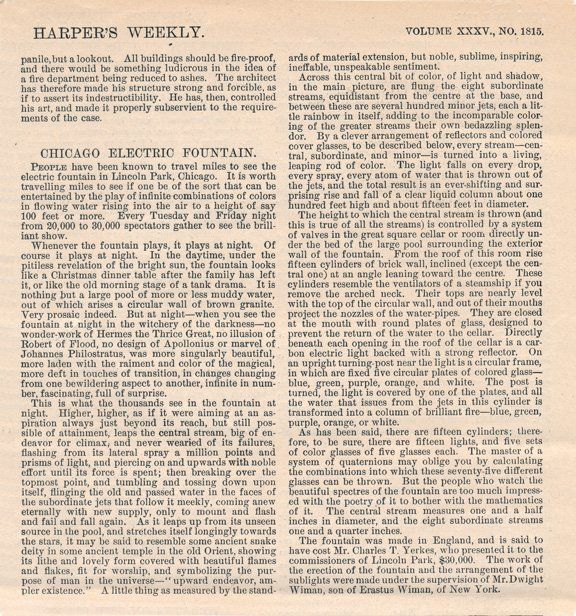

And that brings us to Chicago. A few years ago, I added to the William Butterworth Foundation Archives a page from a Harper’s Weekly dated October 3, 1991. The closing paragraph reads “The fountain was made in England, and is said to have cost Mr. Charles T. Yerkes, who presented it to the commissioners of Lincoln Park, $30,000. The work of the erection of the fountain and the arrangement of the sublights were made under the supervision of Mr. Dwight Wiman son of Erastus Wiman, of New York”.

The late 1880s and early 1890s was a busy period for William Wiman. Check back for the next installment of History Bites Around the Deere Homes to learn about the event that changed William Wiman’s life.

Side note: from “The Electrical World and Electrical Engineer”, Vol. 33, Jan. 5 – March 2, 1899. “The Yerkes electric fountain in Lincoln Park, Chicago has been despoiled of nearly all its brasswork. Sometime during the past week thieves have been operating on the fountain and have carried away over $1,200 worth of brass. In taking away the brass fittings of the fountain they did a great deal of damage than is represented by the value of the brass itself.”

Side note: from “The Electrical World and Electrical Engineer”, Vol. 33, Jan. 5 – March 2, 1899. “The Yerkes electric fountain in Lincoln Park, Chicago has been despoiled of nearly all its brasswork. Sometime during the past week thieves have been operating on the fountain and have carried away over $1,200 worth of brass. In taking away the brass fittings of the fountain they did a great deal of damage than is represented by the value of the brass itself.”

If you have not watched any of our YouTube videos at our channel Deere Family Homes, we encourage you to check out the April 2022 video. The video features the story of one painting hanging in the Deere-Wiman House. The painting’s artist is Alexander Harmer.

We are lucky to have four paintings in our collection that were created by Harmer. It made sense for us to learn more about Harmer and see if we could determine why we have so many paintings from one artist. I love all four pieces and wanted to know more about the artist and determine if there was a connection to the family. Three of the paintings hang in the Deere-Wiman House and one at Butterworth Center. So, it was not just one family member that took an interest in his work.

Did any of the family know Alexander Harmer? We wish we knew. It is possible since Harmer’s life in Santa Barbara does overlap with the Butterworth and Wiman families. Or maybe the family did not know Harmer but was drawn to his art and purchased pieces through art dealers.

Alexander Francis Harmer was born in 1856, in Newark, New Jersey. One source I read said that he sold his first work at the age of 11 for $2. Then at the age of 16, he lied about his age and joined the United States Army. He was stationed in California, which I think is the time period his artistic interests changed. He turned towards painting and illustrating the Apache Nation. The year would have been 1872, and the US Army would have had a large presence in the West with the enforcement of federal Indian policy (which consisted of allotment of land and assimilation.)

After just one year, Harmer asked for a discharge and left the military. He worked as a photographer’s assistant until he was able to enroll in art school. He studied art under Thomas Eakins and Thomas Anshutz at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. In 1881, he re-enlisted in the Army and headed to his assignment at Fort Apache, Arizona. Harmer probably saw the Army as a cheap way of traveling West to continue his interest in the American West and the Apache Indians. During this enlistment, he was able to serve in an Army division assigned to pursue Geronimo. His studies of Indian life created an invaluable record. Harmer then returned to the academy in Pennsylvania where he turned his sketches of the Apache Nation into illustrations for Harper’s Weekly.

Alexander Harmer died on January 10, 1925, supposedly while admiring the sunset from his backyard. This was just six months before the Santa Barbara earthquake, which left the Harmers' adobes in ruins.

Click here to view a new video on our YouTube Channel featuring the Swimming Pool built in 1917 on the Deere-Wiman House grounds. https://youtu.be/NgV6XUEkrLs